One Small Step (or; How to draw an Owl)

This week, my team started a new project. It is only a small piece of work and shouldn’t take long to get into production, I thought. What I didn’t account for was that the team haven’t built anything new in a long time (or in some cases, ever) as our focus has been supporting existing applications for the past year.

To get us rolling, I quickly set up a repository for the code and installed a couple of dependencies for Unit testing and Static Analysis. Just the bare bones so we could start building something. As the team didn’t have a huge amount of experience in TDD, we decided that we would do some mob programming to get the ball rolling and give those less experienced members of the team some confidence in working this way by observing and then trying out some TDD. I was tasked with guiding this mobbing session without being too involved in the process, instead guiding and questioning decisions along the way.

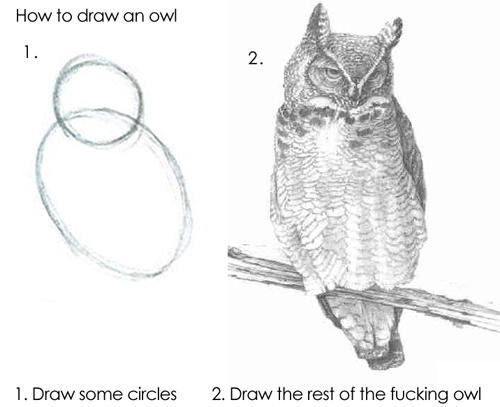

This started out great, we wrote a failing test; made it pass and then… Well, then we tried to draw the rest of the Owl. For those not familiar with that reference, see below;

The problem, like in the above meme was that the feedback loop was far too large. I didn’t want to push the team in a certain direction, rather, I wanted the design to be led by the tests telling us what the next right step was. This, I thought, would help to highlight one of the main benefits of TDD. Unfortunately, when the steps are too big, we often jump to conclusions and try to write code that isn’t yet required. The ultimate result of this was that the design missed the mark as the team didn’t tease out the correct data structure by thinking about and writing tests, instead they wrote a single test, then tried to write all of the application logic based off that one test. The work was no longer iterative but was reliant on a large fixture set that mapped out the expected result in full.

For example, one of the class’ simply had to build a calendar like structure. Where given a day of the year, we either have an object of data to store, or we don’t. Those are our two most simple test cases and could get us rolling with a design straight off the bat. One might decide to structure this data like below with a single entry for each day of the year.

{

"2023-01-01": {},

"2023-01-02": {},

"2023-01-03": {

"data": "Something",

"price": 20.00

},

"2023-01-04": {},

}

Instead, because we didn’t respect the TDD cycle, we ended up trying to structure the data in terms of numeric keys for days of the month (from 1 through 31), within each these we had an entry for each month of the year, and then within each of those keys, we stored either an object of data or nothing like so;

{

"1": {

"January": {

},

"February": {

},

"December": {

}

},

"2": {

"January": {

},

"February": {

},

"December": {

}

},

"3": {

"January": {

"data": "Something",

"price": 20.00

}

}

}

As I’m sure you can appreciate, this structure becomes really unwieldy very quickly. Not to mention the extra work required here around how the calendar will be built taking into account month lengths and leap years. The first structure on the other hand is really easy to create using a PHP DatePeriod object to define what we mean by a year. This simplifies our implementation significantly and also makes the data easier to reason about.

The key thing here is that the team had fixated on their idea of what the end product should be and tried to build it with tests being somewhat of an afterthought or necessary evil rather than a tool to help them think about use cases and how to keep the design testable and easy to change if we followed an unfruitful path.

Another key misstep (although not directly related to the theme of this post) is that although there were a couple of opportunities brought up during the mobbing session to go back to the PO and suggest a simpler solution to this problem that could allow us to deliver value on this project more quickly, albeit with a slightly different (but still meeting the brief) implementation, no one took the initiative to do so.

In my experience, POs are often receptive to developers’ ideas on how we can deliver value, faster and all it takes in these instances is to open up a dialogue. We would no doubt end up with better products if more developers took it upon themselves to offer solutions to problems rather than implementations of solutions given to them by their partners in product.

Writing this post has even given me another idea on how to simplify this project even further so I will be looking to get sign off from my PO on altering the spec slightly in order for us to deliver working software, faster.

I guess the key take away from the experience this week is that shortening feedback loops, whether that is in our practices as a developer or in the way that we communicate with product and business people leads to better software delivered more quickly which ultimately adds business value.